Imagine you’re sitting in a sushi bar in Malibu. Your friend, Clarisse, told you that the California rolls here are to die for. So, every Tuesday, you drive up from Los Angeles just to savor the freshest crab, avocado, and cucumber curled up in the softest of Japanese rice.

When you take your first bite, the taste is so delectable that at first, you don’t notice that Meryl Streep is sitting at the table beside you. Plus, she’s wearing sunglasses—those oval-framed ones from The Devil Wears Prada. Her hair is pulled up in a French toile silk scarf. Kinda like the one she wears around her neck in Big Little Lies.

“My producer and I have been looking for our next star,” she says to you without a hint of irony.

Stunned, you drop your chopsticks.

“We’ve been watching you.” She lifts her chin and gestures to the man sitting across from her. “Donald, our talent scout, is a regular here.” A man sitting cross-legged and sporting a mustache and striped linen shirt winks at you. “And we’d like you to play the leading role in our new film,” she says.

“Me?” You raise your eyebrows and point to yourself. You think how silly that gesture must look. As if there’s anyone else in the sushi bar that you could possibly refer to as: “Me.”

Yes, you.” Meryl says, in her unmistakable cheeky tone.

“Why me?” You hadn’t even auditioned for the part. Is this for real? What are the chances? There you were, minding your own business, dipping nori flakes into soya sauce and about to spend the rest of the evening scrolling through designer shirts on eBay. Now, one of the greatest living actors in Hollywood is holding a script in front of you. She’s making you an offer you can’t refuse.

“You may think you’re ordinary. You may think that you lack the skills,” she says, “but we think you have what it takes.” Meryl lowers her sunglasses. You catch a glimpse of her hazel blue eyes. There’s nothing in them to suggest she’s pulling your leg. “The role demands courage, determination, resilience—and above all—an imagination that’s out of this world.”

Could It Be You?

“That’s me!” you think, bubbling with anticipation. Only yesterday, you were imagining things out of this world. A colony on Mars, a pair of glasses that don’t fog up when you wear a mask. You driving that brand new Aston Martin, and now look! Meryl Streep wants you to be her co-star. Nay, her star! You’re giddy.

Eagerly, but appreciatively, you say “Yes!” You take the script from Meryl’s hands. Her private line is scrawled in ballpoint beside its title: The Ins and Outs of Extraordinary.

For the next several weeks, you spend every minute of your available free time memorizing and practicing your lines until you recite them all by heart. You practice being Extraordinary when standing in front of the bathroom mirror when walking your Goldendoodle when riding the 20 to Santa Monica via Wiltshire Blvd. You go online and teach yourself method acting skills. You get to know Extraordinary in and out. You visualize being nominated for an Academy Award. At times, it’s hard to tell when you’re playing Extraordinary and when you’re just being you. It’s scary and exciting at the same time.

Your friends and co-workers start to notice a change in your demeanor too. You’re dressing better. Holding your head a little higher. Walking with an aura of je ne sais quoi. Everything about you screams—Extraordinary!

Who Would Have Known?

Nine months after that fateful evening at the sushi bar in Malibu, you’ve wrapped up the filming of The Ins and Outs of Extraordinary. It’s been the most extraordinary nine months of your life. Indeed, you’ve been irreversibly transformed by the experience. In less than a year, you’ve gone from spending your nights alone watching Netflix to having your name in lights beside Meryl Streep’s on Netflix’s Top Ten.

Who would have known?

Even if none of it is true—isn’t there something to take away from playing the part? Even if it’s only in your own mind—what’s stopping you from being Extraordinary in the script of your own life?

Identity From the Perspective of Neuroscience

Perhaps one of the oldest questions pondered by philosophers, scientists, and theologians is one of identity: “Who am I?” And yet, two-and-a-half millenniums after Socrates and the Buddha here were are—still without a clue.

Recent studies in network neuroscience suggest that any answer to “Who Am I?” will be inventive. Whoever you refer to as “me,” whatever sense you have of a consistent, uniform, and separate self is a lie! (Or at best, a half-truth).

The storylines of identity never tell the whole story. And yet, we all get trapped in those storylines. Attachment to one or the other inhibits us from exploring the full spectrum of who we are or what we might become.

Isn’t it time to have a little fun with your identity?

Who’s the Screenwriter?

Much of the scriptwriting of our identity comes down to the habits of a large-scale functional brain network called the default mode network, or DMN for short. The DMN is the network most active when you’re doing nothing. It’s the one responsible for your mind-wandering and daydreaming. It retrieves autobiographical memories and fantasizes about your life in the future.

Some neuroscientists call the future-thinking that happens in the DMN “memory for the future.”1 The brain intermingles memories of the past to form notions—or convictions—about what might happen tomorrow. A lot of that prospective thinking goes on below conscious, deliberate awareness. All that habitual neural activity may indeed feel like the baseline of your true self.

In some ways, the ideas that you’re forming about who you truly are aren’t all that far off from your fantasy of playing “Extraordinary” in Meryl Streep’s next film. The difference is that in the “Hollywood fantasy,” you’re aware that it’s a fantasy. You consciously, deliberately role play.

Your everyday identity is, however, no mere fleeting fantasy. It’s an epic one, fleshed out over the years. If you take into account your DNA, parts of your identity even predate “You.” You’ve method-acted “You” your entire life. You’re very good at it. And a lot of the people around you are as convinced as you are that you are really, well, “You.”

To make the fantasy even more believable, you have a whole bandwagon of familial and cultural forces that participate in the formation of “You.” Brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, teachers, mentors. Hell, even the guy at the local convenience store plays a part. You’ve lived through intricate networks of relationships that nurture your identity.

Of course, forming a healthy sense of personal and collective identity is a necessary stage of brain development. Toddlers go through the “ME and MINE” phase. Adolescents tend to identify strongly with genres of music or styles of clothing. Whether it’s punk or ska or rock ‘n’ roll, teenagers like to gravitate towards markers of personal and collective identity. As Peter Burke writes in The Cambridge Handbook of Social Theory: “Identities tell us who we are and they announce to others who we are.”2

Identities also guide human behavior. If you identify with the role of “punk rocker,” you act “punk.” If you consider yourself a “nurse,” you play the part of “nurse.” If you see yourself as Extraordinary, you have no choice but to be extraordinary.

Is Playing “You” Getting Old?

The term “identity” comes primarily from the social sciences. Neuroscientists, on the other hand, tend to take a slightly different approach. According to brain science, at least three factors shape who “you” are at any moment: 1) Incoming sensory input, 2) Recent active memories that give context to the present, and 3) Your long-term memories, conditional responses, beliefs and emotions that influence the way you process that incoming information.3

Be aware that when you feel “stuck” in conditioned responses, emotions, and memories (or a particular identity) there is a way out of the fantasy. You can wake up from the trance.

Why not liberate yourself from any narrow ideas of “You”?

The next time you make predictions of what’s going to happen in the future, don’t base all your fantasies on what’s happened in the past. Have a little fun. Use your imagination.

Even if Meryl Streep doesn’t choose you to play Extraordinary, take pleasure in the thought of it. Cast yourself in the role anyway. Flesh out all the details of your wardrobe. How do you start the day? What do you do when you have a day off work? Do you spend every night on the sofa or do you go on adventures? Honestly, it’s up to you.

Whatever version of Extraordinary you choose, learn the lines. Act the part. Prime your default mode network daily into new conditioned responses, beliefs and emotions. Process the input you take in about the world a little differently—use it all as fuel for your extraordinary life.

And the next time you’re out for sushi, or coffee—sit down at the table as if you were Extraordinary. Order your food as Extraordinary would. Expect that life will be extraordinary because nobody does extraordinary like you do.

See beyond the story you’re telling and the roles you’re playing right now. Instead of enabling those paradigms and habits to control your life, start seeing yourself anew.

Maybe you need to train your imagination a little more?

If that’s the case, do what you so naturally did as a kid. Write a short story and plot a new character for your role in your life. Pen a sequel to The Ins and Outs of Extraordinary.

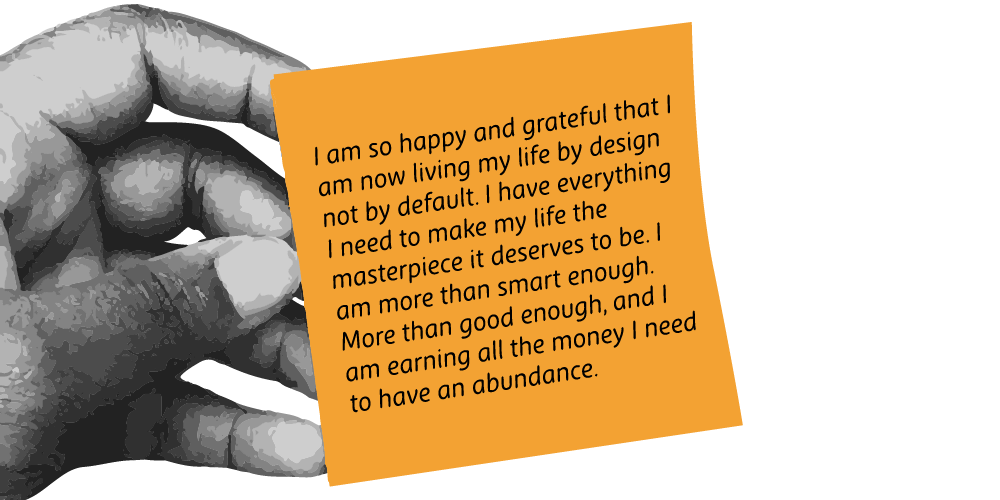

Consider starting something like this:

I am so happy and grateful that I am now living my life by design not by default. I have everything I need to make my life the masterpiece it deserves to be. I am more than smart enough. More than good enough, and I am earning all the money I need to have an abundance.

Now that I’ve given you a head start, write out your “new script.” Give yourself a new role, a new identity, and rehearse it daily—like a Hollywood actor. Before you know it, the part will feel natural. If you can see it in your mind and hold it in your heart, you can create it in your life.

Get ready for You 2.0.

I bet it’s going to be extraordinary.

Endnotes

1. Davey, Christopher G., Jesus Pujol, and Ben J. Harrison. “Mapping the Self in the Brain’s Default Mode Network.” NeuroImage 132 (2016): 390–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.022.

2. Burke, Peter (2020), Kivisto, Peter (ed.), “Identity”, The Cambridge Handbook of Social Theory: Volume 2: Contemporary Theories and Issues, Cambridge University Press, vol. 2, pp. 63–78, doi:10.1017/9781316677452.005, ISBN 978-1-107-16269-3, S2CID 242711319,

3. Davey, Christopher G. et al. “Mapping”

I read every word. It resonates with me as if I had to read this because it was what I needed to learn. I examine myself daily to see how my script is working and teaching me “ I can be all the things I want to be”

I am so happy you like it. Thanks for sharing!

It is a never ending road to keep plugging away, never ending struggle maintaining faith in God that I can do all things through Christ because He gives me strength to accomplish the goals set before me on the path He has me walk making sure that I stick to it.

I do dream and my dreams aren’t that far out of reach. I am worth the effort and I will succeed. Thanks NeuroGym. Love and respect.

Pingback: Unlock Your Inner Genius – John Assaraf

Pingback: How to Stop Fear in Its Tracks – John Assaraf

Pingback: Train Your Brain to Stop Procrastinating- The 4R Process – John Assaraf