Walter White, the antihero of the hit TV series Breaking Bad, starts out with the best of intentions.

An underpaid and overqualified chemistry teacher in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Walter learns he’s been living with terminal lung cancer. Rushed to the hospital after he collapses at his part-time gig washing cars to make ends meet, Walter is determined to secure his family’s financial well-being before he dies.

But like many antiheroes, a series of circumstances lead Walter astray. When he earns a quick fortune using his chemistry skills to cook illegal drugs, he assumes the solution is temporary. But one bad decision leads to another. Pretty soon, Walter’s not breaking the bad habit as much as he’s “breaking bad,” a Southern colloquialism that means “raising hell.”

Throughout the 62 episodes of Breaking Bad, Walter’s character undergoes a nearly diabolical transformation — from devoted family man to ruthless drug kingpin. Adopting the alias “Heisenberg,” by the end of the series, Walter becomes nearly unrecognizable. He’s deteriorated physically and morally.

How can a person go from being so dutifully good to being so hopelessly bad?

The late 19th-century psychologist William James argues that we are all just a “bundle of habits.” Over a century before “neuroplasticity” was all the rage, James wrote about “plasticity” of the ingrained patterns of information in the brain. He attests that while we can break our mental “habit loops,” they nevertheless dominate our lives:

Any sequence of mental action which has been frequently repeated tends to perpetuate itself; so that we find ourselves automatically prompted to think, feel, or do what we have been before accustomed to think, feel, or do, under like circumstances, without any consciously formed purpose, or anticipation of results.

William Jame

Whatever your own “habit loops” may be, you’re accustomed to thinking, feeling and doing things without any “consciously formed purpose, or anticipation of results.” Habit, by its very nature, is effortless. It lacks deliberation. It just happens.

What Are Your Bundle of Habits?

Many of the habits you’ve formed are neither good nor bad—they’re neutral. The habit circuitry of your brain takes cues from your environment, from your sensorimotor sensations. Those cues go on to ignite a sequence of behaviors that help you throughout the day.

Waking up for many people ignites a series of specific actions: drink coffee, brush teeth, check email. Others have purposefully implemented life-changing habits into that routine: meditate, exercise, take a cold shower, or journal.

Habituation, whatever form it takes, is an evolutionary phenomenon. It allows you to perform basic activities without experiencing extraneous demands on your cognition. Forming habits enables you to apply your cognitive reserves towards goals and activities that require them.

Driving a car, for example, involves sequential actions that feel like second nature. When you’re behind the wheel, you turn on the ignition and release the brake. When you back up, you look over your shoulder. If you’re used to manual transmission, you switch gears without thinking of the purpose or outcome of your actions. You just do it. It’s a habit.

Brushing and flossing your teeth is another sequential, self-perpetuating, habitual response. The more you floss your teeth, the less you have to remind yourself to. When you pick up your toothbrush and squeeze toothpaste onto its bristles, you’re likely not forming any purpose behind your actions—it’s just part of your morning routine.

Do Your Habits Have a Life All Their Own?

If you’ve ever tried to kick a habit, you’ve no doubt noticed how frustratingly hard it can be. The same brain networks that help you form a good habit make bad habits tough to break.

If you’re determined to break a social media habit, for example, the associative loop in your brain will put up a good fight against your willpower and good intentions. You may find yourself diligently working away on a project, and wham! Before you know it, a smartphone screen is inches from your face. Your thumb, as if by automation, is scrolling through Instagram.

What just happened? Have you been programmed? Have you trained your brain, through repetition, to automatically check your likes and mentions?

Indeed, you have!

Do bad habits have a life of their own?

Kinda.

Habits often feel instinctual, beyond conscious control. But you can learn to bring your deliberate, conscious—and even playful—attention to any one of your habits. You can learn to be less driven, or imprisoned, by the bad ones. Likewise, you can learn to kickstart good habits and to reinforce them through visualization, repetition, and reward.. You can keep your brain in cruise control when it benefits you. Once you’ve found a happy groove of healthy habits, it won’t take much cognitive effort to maintain your flow.

So how do you leverage the science of habits, so you can kick the bad, kickstart the good, and, well, kick-ass? Before we tap into some of those evidence-based strategies, let’s take a quick tour of the neuroscience of habit formation.

Where Are Habits Formed in the Brain?

There are a few theories of habit formation kicking around. But neuroscientists generally agree that the distinct neural systems that determine your goal-directed behavior and your habitual behavior interact.

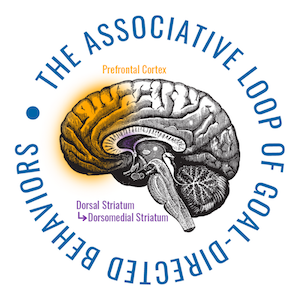

Both habitual and goal-directed behaviors involve two areas of your brain: the cortex and the striatum.

The cortex, as you may know, is the outer layer of your brain. It plays a key role in your ability to remain attentive and aware. It’s where you process many of your thoughts and memories. It’s where the executive of your brain “lives.”

Your striatum, on the other hand, is part of an area called the basal ganglia, which is evolutionarily part of our “ancient”, or some say “primitive,” brain. Recent research has demonstrated that your basal ganglia mediates distinct types of learning and memory. When you plan physical actions in the world, make decisions, feel motivated, experience reinforcement, or perceive rewards — your striatum plays a part in it.

But if goal-directed and habitual behaviors both involve the cortex and striatum, what differences lie in the neural activity behind each?

Goal-directed behaviors involve an associative loop that runs among key areas of your prefrontal cortex involved in decision-making and those in your dorsomedial striatum (DMS), which mediates your ability to stay cognitively flexible and participate in action-outcome learning.

Habitual behaviors, on the other hand, engage your sensorimotor cortex (which integrates sensory and motor signals necessary for movement) and your dorsolateral striatum or DSM (which receives input from the somatosensory and motor-cortical regions and initiates sequences of behaviors).

Habitual behaviors depend more on your sensorimotor systems than do goal-directed behaviors. To form and break habits, therefore, you need to learn to not only be conscious of them but to fully and mindfully engage your senses and movements in both forming them and breaking them.

Since the two circuits of goal-directed behaviors and habitual behaviors are so intertwined, an effective way to kick bad habits and kick start new ones is to train yourself to quickly, efficiently, and consciously switch from one to the other.

Further, you need to practice turning off your cruise control mind and making conscious decisions by engaging in action-outcome learning.

A Quick Innercise™ For Breaking Bad Habits and Breaking Into Good Ones

- Take a few conscious, relaxing and centering breaths to get your mind focused. The less stressed you are, the less likely your brain will offload cognition to its habitual neural circuitry.

- Once you feel steady, focused, and relatively calm, write down a list of 2-5 bad or destructive habits that you’d like to break.

Choose ones that are holding you back from fulfilling your dreams, achieving your goals, and living your best life. They might be everyday habits like drinking too much coffee and not exercising enough. They might be lethal habits like smoking. Or they might be inner habits of mind, like believing in your negative self-talk or ignoring your intuition.

- Calmly, objectively look at those bad habits. Write down the circumstances and environments that you associate with those “bad” behaviors.

If it’s smoking, you may notice that certain locations in your home, workplace, or neighborhood encourage you to light up. It may be triggered when you have a glass of wine. If it’s too much coffee, a route near a favorite coffee shop often may trigger your caffeine habit.

- Write down the specific sequences of actions that arise automatically when you enact those bad or disempowering/destructive/excessive habits.

This step helps you to develop your skills of awareness. Perceive the cues, triggers, and the specific sequences of how you normally feel and behave. If you suffer from a seemingly inescapable coffee habit, your habitual sequence might look like this:

- You feel a little tired and notice you need a break from work.

- You remember the delicious taste of freshly-made espresso and the jolt and comfort it gives me in the morning.

- You move to the espresso bar in your kitchen.

- You grind the espresso beans in the burr mill, savoring the scent.

- You scoop the grinds into a portafilter basket and tamp them down.

- You click the portafilter into place, making sure it’s snug.

- You turn the handle, listening to the sound.

- You watch the fresh espresso dispense into my favorite cup, in sweet anticipation.

- You pour the deliciously anticipated espresso into your cup anxiously awaiting to take the first sip.

5. Remaining in a calm mental state, visualize yourself in those environments where you feel triggered to enact a bad habit. Notice any compulsions you might feel to buy a pack of cigarettes or drink another cup of coffee.

6. Imagine the negative consequences of following through with whatever bad habits you’ve formed. Doing that will reinforce your goal-directed circuitry and motivate you to act against those negative consequences.

7. Now, interrupt the automaticity of that behavior. Shift your attention swiftly towards a goal-oriented behavior. Start making some conscious positive decisions. Feel empowered by that switch.

8. As you consciously interrupt the flow of automatic negative behaviors—bring your pleasure and reward circuitry online. Focus on the PLEASURABLE feelings associated with any positive goal-directed behaviors. In essence, REPLACE your negative habits with REWARDING goal-oriented thoughts, emotions and behaviors.

9. Write down an easy replacement behavior, one that helps you work towards your goals but is also pleasant or fun to experience.

10. Savor the positive results of following through with the new good behavior.

Taking our coffee habit, the new, conscious sequence of actions, which include interruption, integrating a pleasurable replacement behavior, and savoring and celebrating it might look like this.

- You feel a little tired and notice you need a break from work.

- You remember the delicious taste of freshly-made espresso and the jolt and comfort it gives you in the morning.

- Pause to imagine if there’s any other way to take a break and feel energized.

- Make a list of other beverages that are also delicious, freshly made and energizing: Matcha green tea, sparkling water, freshly-made juice, etc.

- Choose one and savor the process: take in the scents and sensations just as I would my coffee.

- Imagine the antioxidants of the green tea entering my cells and rejuvenating me. Feel the pleasurable satisfaction of hydration inherent when drinking sparkling water. Smell the green earth mingled with the carrots as I juice them one by one in my juicer along with apple, cilantro, lemon and ginger.

Each time you overcome your bad habit, pat yourself on the back. Celebrate your Einstein brain. Say: “Bravo. I’m living my best life!”

Remember: when it comes to the neuroscience of kicking and kick-starting habits, it’s important to reinforce your learning. Reward yourself with small wins every time you break up, even a little, with an unhealthy habit and adopt even the tiniest changes in your routine. Celebrating tiny wins will increase the level of dopamine in your brain, which increases your overall ability to learn and to stay motivated.

How might you celebrate? Well, that’s partly up to you. Everyone likes to celebrate in their own way. You can give the air a “high-five.” You can invent a special handshake that only you and your poodle know. You can do the old Tiger Woods “fist pump” to celebrate or 3give yourself five minutes of browsing your favorite online shop or Pinterest account. It’s all up to you! What brings you just a little joy and a feeling of reward?

Take a different route than Walter White, aka Heisenberg. Choose tiny actions and celebrations that increase your stamina, your income, and your relationships. Just pay attention to the tiny shifts and sequences that go into forming and reforming habits. Like tuning the parts in your inner engine, sometimes the tiniest fix goes a long way!

Endnotes

1. Jame, William. Habit. London: Read Books, 2013.

2. Goodman, J., and M.G. Packard. “Memory Systems of the Basal Ganglia.” Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience, 2016, 725–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-802206-1.00035-0.

3. Mendelsohn, Alana I. “Creatures of Habit: The Neuroscience of Habit and Purposeful Behavior.” Biological Psychiatry85, no. 11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.03.978.

I recently noticed two short-term habits which, when I changed /stopped doing them, my body had to adjust/“go conscious.” This was fascinating to me.

The first habit of one month’s duration was watering vegetable starts by hand morning & evening. Yesterday I planted these starts in my raised bed & yet my body “missed” tending to them on our terrace evening & morning. I felt it physically.

The second habit was 3 months of having to drive 20 minutes to feed, water & clean up manure of my horse morning & evening. It was a lot of responsibility, impacted my social life & caused a level of anxiety. I moved my horse elsewhere a week ago where she is completely cared for. This was a blessing but my body continued to feel anxiety for a few days at Yhe times I had been caring for her. It was almost as if I “ missed” the negative tasks.

I wonder what you make of this?

Pingback: How to End Self-Sabotage – John Assaraf