Almost Every human alive has at one point or another tried to start a new empowering habit (New Year’s resolutions) or stop a negative disempowering habit. There might be one you’re working on right now. With all the effort we humans make, why is starting or stopping a habit so difficult for so many of us? What if by understanding your brain better and applying some simple, neuroscience-based techniques, you can be a master of change by mastering your habits?

Habits and Their Formation

First, you must understand that your brain (every brain) strives for survival and stability (homeostasis), and it processes external and internal events in ways that help bring about that result. It does this while trying to conserve its most precious resource: energy. In essence, your brain wants to do what is easy and energy-saving, rather than what is hard and energy-demanding. In service of that purpose, you form habits.

Habits are automatic behaviors. They’re automatic in the sense that they don’t require thought and attention, which are expensive. The reason they consume less energy than plans and decisions is because commonly used patterns of neural communication become more efficient with repetition. This makes sense because your repeated behaviors are presumably valuable (Why else would you repeat them?). So it’s much more efficient for your brain to “hard-wire” valuable behaviors (automate them) than it is to expend precious cognitive resources thinking about how and why to do them each and every time. So conservation and efficiency are the critical components of the brain’s game.

The Potential for Change

Habits are triggered by cues that occur in certain situations (hitting the gas when the light turns green, lighting a cigarette when you feel stress), and you don’t need to be conscious of a goal to perform them [1]. The good news is that once you’re aware of a disempowering habit, then ending it (aka, habit extinction) is possible – even if you’ve had it for a very long time. This is the subject of a lot of rodent research, where researchers manipulate the environments of “subjects” to cause behavioral changes [2]. Lab rats can’t evaluate their own lives and behaviors and decide to make changes and improve their lives – as far as we know, at least. Humans, however, are a very different story. You can choose to study yourself. You can become your own subject and create the changes you want to see. You can absolutely do this if you are self-aware and committed to living a better life.

Once you become aware of a habit and the effects it has on your life, you have a decision to make. If you identify a habit and you’re OK with things as they are, you can leave it alone and enjoy the pleasant internal chemistry (e.g., oxytocin, natural opiates in the body) and parasympathetic response (e.g., low stress, relaxation) of having no resistance to overcome [3]. But when you see value in changing a habit (getting something you want, avoiding something you don’t) and decide to take action, your brain – your prefrontal cortex, in particular – is in high gear. Let’s dive into that.

Reward

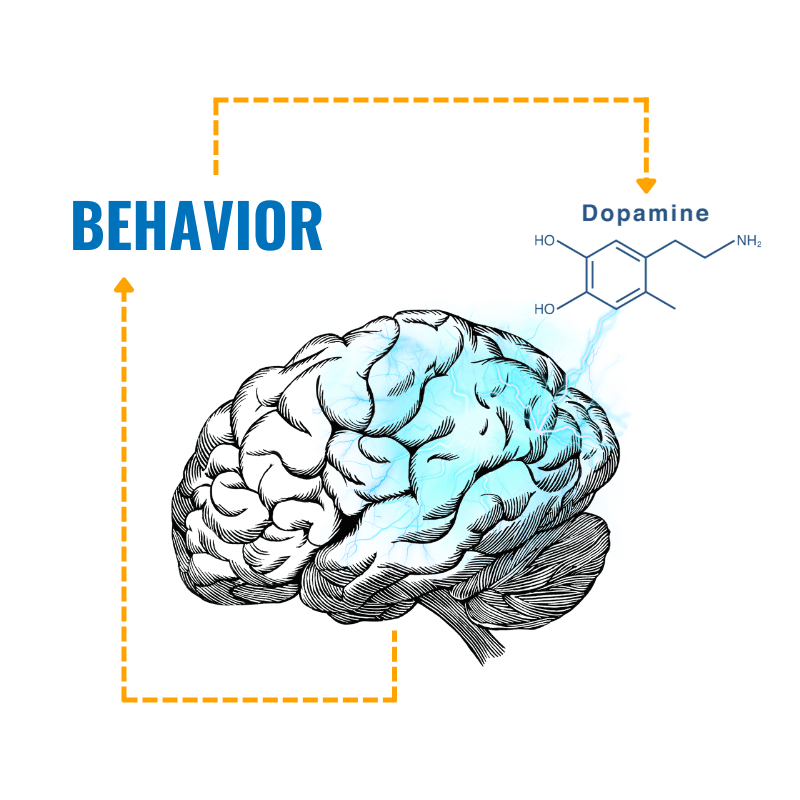

Dr. Eric Kandel and his colleagues won a Nobel Prize in 2000 for showing that even sea slugs (20,000 neurons vs our roughly 100 billion) learn through rewards [4]. A huge driver of this is a chemical messenger in the brain (neurotransmitter) called dopamine. The amount of dopamine in your prefrontal cortex increases when a reward occurs, which then promotes learning and the motivation to get that reward again [5]. Thankfully, the patterns of neural communication in your brain never completely lose their flexibility, and dopamine helps change them [6]. So your brain never becomes completely rigid. This ability of your brain to learn, grow, and adapt throughout your whole life is called “neuroplasticity”, and it’s one of the greatest discoveries of the last 100 years – maybe ever! Neuroplasticity is the reason that the change you want for yourself is possible, and consciously manipulating your rewards is a powerful way to set that process in motion.

Rewards drive behavior whether you’re aware of it or not. Every time you check your messages, eat a potato chip, drink a beer, or turn on your TV, you get a reward [1]. Rewards can happen when you satisfy a craving (smoking a cigarette, eating a candy bar), or when you avoid something unpleasant (avoiding working on an upcoming presentation you’re afraid to give). Rewards can also come from avoiding things that are new and uncertain, like deciding to skip a social function where you won’t know anyone.

You see, habits, whether they’re good or bad, provide comfort and predictability, and your brain loves that. Change is scary. It costs energy. So even when a new behavior seems like it could be rewarding to you, there’s resistance from the inside. But remember that it’s your brain. You get to decide which habits you want to keep, modify, or eliminate based on how well they align with the life you choose to live. You just need the right skills, tools, and motivation.

Value and Motivation

Let’s say that you’re aware of a disempowering habit and how it’s negatively affecting your life. First, that’s great! Awareness of a problem is the first step toward improvement. Now that you know what you’re dealing with, you can use the power of your mind to imagine what it would be like to choose a different behavior [1]. Really do that now:

- What rewards would you have if you changed?

- How would you be better?

- Who besides you would benefit?

- Most importantly, do the benefits of change outweigh whatever you’re getting out of the old habit?

Let that last one really sink in. Be honest with yourself. If the answer is yes, then you can make a plan and create the change you want. Let’s learn more about the how and why.

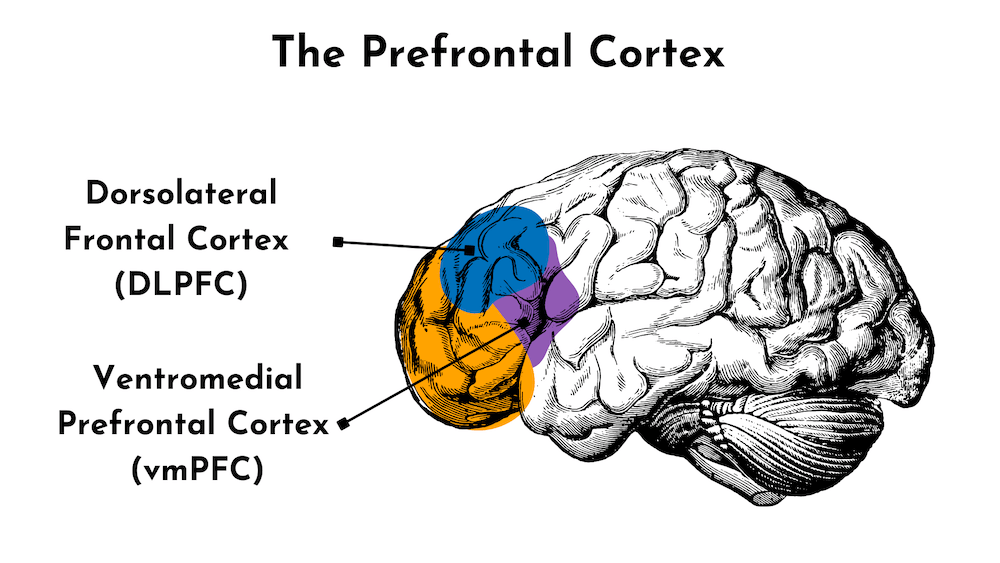

How do we know habit change is possible, and how does it play out in the brain? There’s a region in the front of your brain called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), and it’s critical for motivation [7], including the motivation to disrupt homeostasis (stability, sameness) for the sake of a positive change. The vmPFC receives information about the relative values of your potential options for behavior. You can think of this like a rating system (“Is A a better option than B? Is B better than C? Is D better than all of them?”). The vmPFC then passes that information along to other parts of the brain [8]. These regions include the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), one of your brain’s main decision-making regions. An example of the DLPFC in action is a decision to not indulge in potentially harmful cravings, like unhealthy foods or harmful substances. Because of your DLPFC and the prefrontal cortex in general, you can be aware of a craving and judge that the reward of satisfying it is outweighed by the much greater rewards (health, longevity, attractiveness) of not indulging it. This overall process is an example of your prefrontal cortex being used to improve your life. Based on this process, it’s easy to see the importance of attaching a high value to a new empowering behavior.

For a new behavior to become a habit, you have to be very clear with yourself about its value, and you have to remind yourself of it often so that you can hard-wire the need for it. You have to know why you want it and really feel how important it is that you have it. The more value you put on the reward of sticking to a new empowering behavior, the more motivated you’ll be to solidify your change for the better [7]. Basically, you must magnify the value of the new habit and minimize the value of the old one so that the balance between the two shifts heavily in favor of the change you want – that you must have.

There’s another crucially important point about motivation that we need to talk about, and it’s this: If you think about a positive behavior as being part of your identity and not just an action you should perform (who you are, vs. something you should do), then that behavior will be more motivating and you’ll be more likely to do it [7]. For example, if you (A) tell yourself that you exercise because you’re a strong and healthy person (identity), instead of (B) thinking that exercise is something you should do because it’s good for your health (action), then you’ll be more likely to make a habit of it.

How we see ourselves is an extremely powerful motivator. Everybody wants to believe they’re a good, strong, valuable person, and nobody wants to believe the opposite. Using this knowledge to your advantage gives you a valuable leverage point for ramping up motivation and reshaping your life.

Steps You Can Take Today

Now we come to a few simple, easy things you can start doing right away. If you stick with these incremental changes and add others as needed, they’ll snowball into truly transformative changes.

Change your cues

If you take away the cues that cause you to engage in a behavior you don’t want anymore, then you remove a key component of the habit cycle. It’s like draining the gas from a car’s tank. For example:

- If you want to stop eating fast food on your way to or from work, take a different route.

- Or, by the same token, you can create new cues to trigger new habits that you want to form:

- Set an alarm to turn off the TV each night.

- Put a glass of water next to your bed at night so that you see and drink it first thing in the morning.

Stack positive habits

Use existing habits that you don’t want to change as cues for new habits that you want to form:

- Repeat positive affirmations each morning while you brush your teeth.

- Think of 3 things you’re thankful for every morning when you sit down with your coffee.

Habit replacement

When you feel the urge to engage in a bad habit, do something else!

- Sing your favorite uplifting song to yourself when you start craving sweets.

- Review your goals for the day when you start to feel frustrated in traffic.

No matter what it is that you want to end, begin, or change, consistency is the key. Repetition makes all the difference, and ultimately, it will make the changes you desire solidify into habits that serve you. If you want to learn more about how to reshape your habits so that you gain constant momentum toward your goals. If you want to go deeper on how to manage and master your mindset.

Conclusions

The main takeaway here is that you can, in fact, use your conscious mind to alter your brain’s “programming” for the better. You can choose to change your code. By placing the highest values on the behaviors that serve your goals, and by repeating and hard-wiring new thoughts, emotions and behaviors, you can deliberately create habits that will work for you.

The rewards of new behaviors cause learning. That’s the same way your outdated, unwanted habits are formed. The more you repeat new behaviors, the less attention, and effort they’ll require until they too become automatic. That’s what we really want. Once a new habit is locked in place, your brain will attempt to maintain stability just like it did with the old habit. Now, however, it’ll do that in service of goals you’ve actually chosen for yourself.

You don’t have to continue wasting your time and energy repeating bad habits that formed before you had the knowledge and skills needed to choose and implement your own. If the cost of leaving “well enough alone” is clear in your mind, and if you feel like a change is needed, then change can be yours. You can be the person you want to be. You just have to be committed.

If you want to go deeper on how to gain more confidence and certainty to master your life, pick up my newest bestselling book Innercise: The New Science to Unlock Your Brain’s Hidden Power.

Endnotes

1. Brewer, J. (2019). Mindfulness training for addictions: has neuroscience revealed a brain hack by which awareness subverts the addictive process?. Current opinion in psychology, 28, 198-203.

2. Bouton, M. E. (2021). Context, attention, and the switch between habit and goal-direction in behavior. Learning & Behavior, 49(4), 349-362.

3. Michaelsen, M. M., & Esch, T. (2021). Motivation and reward mechanisms in health behavior change processes. Brain Research, 147309.

4. Drachman, D. A. (2008). Memory and the brain: Beyond intracranial phrenology. Current neurology and neuroscience reports, 8(4), 269-273.

5. Arias-Carrión, O., Stamelou, M., Murillo-Rodríguez, E., Menéndez-González, M., & Pöppel, E. (2010). Dopaminergic reward system: a short integrative review. International archives of medicine, 3(1), 1-6.

6. Müller, P., Rehfeld, K., Schmicker, M., Hökelmann, A., Dordevic, M., Lessmann, V., Brigadski, T., Kaufmann, J., & Müller, N. G. (2017). Evolution of neuroplasticity in response to physical activity in old age: the case for dancing. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 9, 56.

7. Berkman, E. T. (2018). The neuroscience of goals and behavior change. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 70(1), 28.

8. Hare, T. A., Schultz, W., Camerer, C. F., O’Doherty, J. P., & Rangel, A. (2011). Transformation of stimulus value signals into motor commands during simple choice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(44), 18120-18125.

I was so helpful reading this and opens up mind on step to follow on achieving my goal because changing an habit is not easy at all.

Excelence!!!

This makes so much sense..im in need of happiness..i am working on it. Thanks!!

Pingback: Train Your Brain to Stop Procrastinating- The 4R Process – John Assaraf